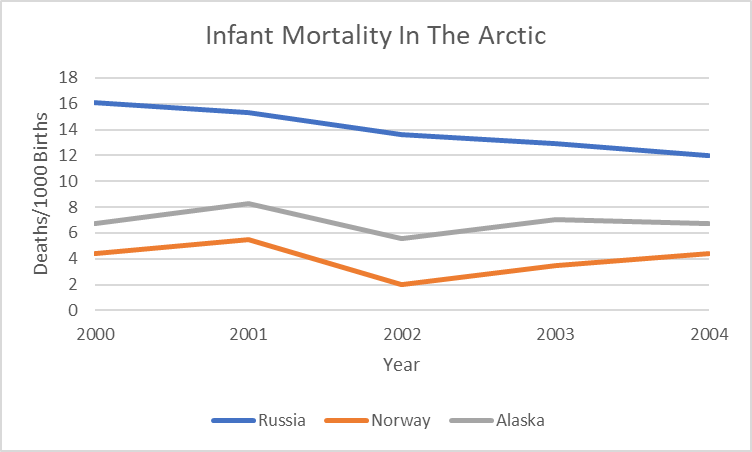

I created my graph based on data from ArcticStat gathered between the years of 2000-2004 on the infant mortality statistics of three Arctic nations- Russia, Norway, and the United States (Alaska). One challenge I encountered was that the data was not always organized the same- some countries listed it by regions, others offered total statistics. I decided to standardize my numbers and take the national totals of each country for each year. To acquire the total statistics for both Russia and Norway, I had to take the average across four Arctic ‘okrugs’ in Russia and three Arctic counties in Norway. To do this, I simply added the regional statistics together and divided them by the number of counties sampled. The Alaskan statistics were already totaled together.

According to the Arctic Human Development Report (ADHR), published in 2004, infant mortality is one of the many indicators of community health across the Arctic. This is part of the technology aspect of Arctic health, as immunizations and community medical care advancements have greatly improved care for mothers and infants across the Arctic. Other contributing factors to infant survival include regular food resources, good water quality, and accessible public services. Globally, the health of infants is an important indicator of both the child’s future life expectancy and the state of medical care in the region in question. Good pre and post natal care indicates more advanced healthcare as a whole.

In this particular graph, I am comparing the infant mortality (deaths/1000 births) across Russia, Norway, and Alaska for five years starting in the year 2000. Overall, Norway has the lowest infant mortality and Alaska’s is slightly higher. Russia’s infant mortality is almost double that of the other two nations. However, while Norway’s and Alaska’s rate fluctuates and is the same at the beginning and end of the five years, Russia’s infant mortality trends steadily downwards during the five year period of analysis. These trends make sense based on some general context in each nation. Norway, with universal healthcare and high rates of medical research and development for Saami people residing in the three northern counties, logically had the lowest rate. Alaska, which has no universal healthcare, and high treatment costs, had higher mortality. Norway and Alaska have both focused extensively on the eradication of tuberculosis through vaccination and community health programs, leading to lower infant mortality due to vaccines. Russia, on the other hand has not been as effective at controlling tuberculosis and does not have adequate vaccination programs. This is not the only reason the infant mortality rates in the Russian Arctic are sky-high, the issue has to do with the national state of healthcare which is exacerbated in distant regions such as in the north. The early 2000’s, when the data was taken, were a time of cultural and social upheaval in Russia as people struggled to remake order and government in the country. Many public sectors suffered, including healthcare, which to this day is severely understaffed, underfunded, and corrupt. While there is stronger national control at the center of the nation, remote places in the north and south of Russia have little oversight or funding which significantly affects the quality of care available. Over the five years, the infant mortality trends in the Russian Arctic improved, but this was in line with national trends of health improvement as society settled into new patterns.